Laowai Chinese has moved

Due to perpetual banning and unbanning by China, this blog has moved. Please update your bookmarks to point to the new site: www.laowaichinese.net

Due to perpetual banning and unbanning by China, this blog has moved. Please update your bookmarks to point to the new site: www.laowaichinese.net

Due to perpetual banning and unbanning by China, this blog has moved. Please update your bookmarks to point to the new site: www.laowaichinese.net

Posted by Albert at 1:51 PM 0 comments (click here to leave one)

(I don't know why the "hǎo" in the title looks dumb in Internet Explorer...sorry)

Well, for whatever reason, the blog is back up in China. So please destroy any links to the pirated pkblogs.com version (as I have done).

Here's some appropriate vocabulary to celebrate with:

hǎo xiāoxi = good news

huài xiāoxi = bad news

I actually think of that "xiāoxi" should as "information" or "message." If you want to say "read the news" it's a different word:

kàn xīnwén = read the news [look new + smell/hear]

Weird that "to smell" can also mean "to hear." And, even though it's not SUPER important, the correct measure word for both kinds of news seems to be "tiáo" {measure word for long, narrow things} according to Chubby. Doesn't really make a lot of sense, but I always imagine ancient Chinese messengers reading decrees from the emperor on long scrolls (remember ancient Chinese was written top to bottom, right to left). But thankfully, they actually seem to prefer the old "ge" measure word in this case:

wǒ yǒu yí gè hǎo xiāoxi = I've got good news [I have one {m.} good message] **better**

wǒ yǒu yì tiáo hǎo xiāoxi = I've got good news [I have one {m.} good message]

Don't be alarmed that the tone for "yi" changed. That's what it does. There's a post in the works about the tone changes.

It's apparently also ok to say

wǒ yǒu hǎo xiāoxi = I've got good news [I have good message]

But omitting the "one" part of it seems to imply that you have a whole bunch of news to share. And, more importantly, the Chinese usually have that measure word in there when they say it and hey...they're the boss.

And now that final step of integrating the vocab into my daily life:

wǒ yǒu yí gè hǎo xiāoxi: wǒ de bókè huílái le = I've got good news: my blog came back

Posted by Albert at 6:11 AM 0 comments (click here to leave one)

Topics: General, Vocabulary, Word Hog

If you're able to read this you should be as glad as I am. It seems that China has, for whatever reason, blocked access to all blogger/blogspot blogs. I think the email updates should still be going out. But if you're in mainland China (I still haven't heard from that island off the east coast) you won't be able to access it directly.

Regardless of what context may suggest, "zěnme bàn?" doesn't mean "how did they ban me?" It's the bàn of bànfǎ = method [do way]. A good translation would be:

zěnme bàn? = what's to be done? / what should we do?

I used that the other day when my water dispenser sprung a leak. The guy delivered a new bottle and I showed him the puddle. He then waxed eloquent, totally losing me, saying things I'm sure boiled down to stuff like:

"Well this particular model, when inundated with an influx of new water after a freshly replenished container is installed, seems to have a tendency to backwash ever so slightly, while, I shouldn't fail to mention that, a simple preemptive strike--viz. draining the surplus water before installing the new jug--may very well serve to nip this problem in the bud."

I blinked at him loudly and said simply, "zěnme bàn?"

He then sprung into action demonstrating and implementing what he had (I'm sure) just explained and all was made clear. Never mind that it didn't solve the problem. I called him the next day saying:

hái yǒu yíyàng de wèntí. zěnme bàn? = (it) still has the same problem. What should we do?

The point is, this is a useful little phrase that, even if it doesn't lead to a real solution, might at least lead to action.

Which brings me back to the problem of this blog. Here's what I suggest:

Posted by Albert at 6:23 AM 0 comments (click here to leave one)

Topics: General, Vocabulary, Word Hog

Even though it might seem like a no-brainer to you, enough people have commented on my little notebook that I thought it merited a short post.

I rarely leave home without my little notebook:

Organize it however you want, but I strongly recommend carrying a field notebook whenever Chinese interaction, or even dead time that you might want to use as study time, is on the horizon.

Posted by Albert at 9:39 AM 0 comments (click here to leave one)

Topics: General, Vocabulary

See also MDBG Online Dictionary - Tutorial

Having looked at most of the major online Chinese-English dictionaries, there is absolutely no contest as to which is the best for laowai trying to learn Chinese.

There are two ways to get to the MDBG Chinese-English dictionary:

www.xuezhongwen.net (easier to remember)While it might be confusing to get past the first screen, the actual user interface is by far the simplest out there. Other dictionaries are so cluttered I sometimes don't know where to type my query.

that let's you see literal translation for every hanzi character in an entry

that let's you see literal translation for every hanzi character in an entryPosted by Albert at 4:01 PM 6 comments (click here to leave one)

Topics: Resources

See also MDBG Online Dictionary - My review

There are two main ways to use the dictionary:

I always start with the Basic Word Dictionary (even though sometimes I end up using some Advanced Word Dictionary tools).

You can input English, pinyin, hanzi or combinations into the Basic Word search box. I'll talk about hanzi entry below. Here's how the English and pinyin inputs work.

Examples:

You can display the tones as "you4" or "yòu." I prefer the latter. To change your preference click on the little bubble thing that looks like this:

To really track down those homonyms, you need to be able to do smart searches. Otherwise, a search for "you" will get you all the pinyin "you" entries AND the English "you" entries on one page.

Examples:

If you dump some hanzi into the Basic Word Dictionary page it will try to find a single definition. But, if you've thrown a whole sentence, or a line from a song (like this  ) in there, it will give you the following message:

) in there, it will give you the following message:

By all means click that and you'll be taken to a nice warm place where a wise old man will explain what each word means...or at least a page showing the results.

Now, let's find out what that "lao" in "laohu" really is. Click on the little scissors tool  to separate the "lao" from the "hu"

to separate the "lao" from the "hu"

Now you should be on a page that shows the exact meaning of "lao" and "hu" separately. Let's follow the trail a littler farther. Click on the isolated hanzi character for "lao" (looks like this  ).

).

Now you're on a page that has all sorts of info about that character including the Cantonese pronunciation.

Look at the far left side of the table and you should see this:

If you want to know how to draw the character (brush strokes and all) click on the little paint brush.

If you want to see every entry in the dictionary that contains that character, click on the huge hanzi character on the far left.

This little rabbit trail has actually taken us through some of the Advanced Word Dictionary pages without our knowing it. This can be a good way to figure out what all the little pieces mean, especially if you're trying to weave a hanzi web in your brain.

Posted by Albert at 4:00 PM 0 comments (click here to leave one)

Topics: Resources

To really speak Chinese, you have to master the tones. But, most laowai don't.

It's a good idea to learn the tones as you are learning vocabulary.

The problem with learning Chinese vocab is there are really two things to remember for each word:

These two parts are totally disconnected. Much like learning irregular verbs in English, or the gender of words in German, the tones are completely arbitrary and, to us, random.

A friend found that his Chinese progress was really slow because he was trying to learn the tones from the get go. So he ditched them in attempts to master at least the phonemes for each new vocabulary word. It worked and he burned up the trail learning new words. But, he found people often didn't understand him and it was quite difficult to add the tones back into the mix later. I still believe it's best to integrate learning the tones from the very beginning.

Here are some strategies to master the tones:

The tones are usually referred to in this way:

Once you learn how to say each tone, then associate some emotion with each one. For example, here's my own personification and characteristics for each tone:

To reinforce the visual images of tones, you might want to label your house.

This trick requires a native-speaker informant who speaks good Mandarin and a tape recorder. I wrote a bunch of useful little phrases like:

Then, I recorded my Chinese friend saying them. I tried to mimic the rising and falling of the phrase as a whole without caring one fig for the tones of individual words. This works really well since these kinds of phrases seem to have fairly set intonation.

Teddi actually drew a "crenulated castle wall" diagram of each phrase to have a visual representation of the ups and downs of the utterance. Maybe I can persuade him to contribute one or two to this blog as samples.

This is a last resort that I'm had to, well, resort to several times. The reason this works is the Chinese themselves seem flatten out fudge on tones of individual words in rapid speech. So, if I'm not sure of a particular word's tone (and hopefully that's not the most important word in my sentence), I just breeze over it and hit the tones I know nice and solid. It doesn't always work, but it's often better than slowly and methodically saying the wrong tone for a word when you're not sure.

These are just examples. You can be as creative as you want as you make "donkey bridges" and think of tricks to beat the tones into your brain. Just get those little tones learned by hook or by crook.

See the tones. Be the tones. Make it happen.

Posted by Albert at 9:06 PM 1 comments (click here to leave one)

Topics: Pronunciation, Vocabulary

shuāng yǎnpí = double eyelid

I learned this word at lunch yesterday. Apparently most westerners have it, and not all Chinese do. The Chinese seem to think it's a beautiful feature. Somehow, it doesn't sound beautiful when I say it...oh well. Here's some more info on the physiological phenomenon.

Posted by Albert at 7:23 AM 1 comments (click here to leave one)

Topics: Vocabulary, Word Hog

tèbié = especially, special, exceptionally

NEWS FLASH: They often just say tè

I just got fruit from one of my usual fruit dealers. The competition is so fierce between the fruit ladies that they usually throw in an extra apple or orange to try to secure my business for next time. Here's how it went:

A = Albert

F = Fruit Lady

(F tries to give a free piece of hāmìguā)

A: bú yào, xièxie = I don't want it, thanks.

F: sòng gěi nǐ = I'll give it to you for free

A: bú yào, háishì xièxie = I don't want it, thanks anyway.

(F puts in the the bag)

F: zhège tè tián = this one is especially sweet

But often they don't use tèbié the way we would use "especially." We say especially to mean, "in comparison to other things (usually just mentioned)." For example, "I saw 3 movies but I the the third one was especially good."

The way I'm hearing it used is more like the way we say "really" or "SO." I heard a student describe a lecture (not mine) as:

tè wúliáo = SO boring

Another student celebrated her triumph in killing a mosquito by calling it:

tèbié bèn = especially stupid

If anyone knows any rules for when you can say tè and when you should say tèbié, please leave a comment below.

Posted by Albert at 12:54 PM 5 comments (click here to leave one)

Topics: Vocabulary, Word Hog

During my first year in China, every Chinese person who came to visit me was guaranteed hours of entertainment. All they wanted to do was walk around reading the scores of little post-it notes with pinyin on them.

I labeled everything and it paid off:

I also made a picture of a human body and labeled body parts (I can't draw very well so it was actually really "kǒngbù" (horrifying) as my Chinese visitors put it).

Later I even started writing notes to myself from my imaginary older brother in Beijing. Ping (as I called him) had a key to my house and would come in and leave pieces of advice or warnings like:

Teddi went a step further and posted his lists of "confusing cousins" and "random confusers" above his sink. Whatever it takes to get those tones under your belt.

Tip: buy the real Post-It brand sticky notes. The Chinese-made ones seem to sit in the package plotting little competitions as to who can be the first one to fall off the wall. They don't even stick to themselves when folded in half!

Posted by Albert at 9:12 AM 1 comments (click here to leave one)

Topics: Vocabulary

It's not that we don't have tones in English. No. The tones are hard because English has tones, but we use tone for different reasons.

In English our tones are usually applied to the whole sentence but can also occur on only one word. We use tone to show emotion, attitude, type of sentence (question, statement), etc. As Teddi described it so well: If you asked me "Wanna get some Mexican food?" just think of all the ways I could say, "Fine." A falling tone might mean I really wanted to or that I really didn't depending on how high it started. A rising tone might say, "I want to, but..."

The biggest tone problem I've noticed for laowai learning Chinese is that we project our English tones onto Chinese sentences--especially the final word. The Chinese tone we know (or maybe don't know) is correct for that word is fighting in our mind against the tone we WOULD put on the word if it were English. It just feels weird to end a question with a declarative sounding falling tone as we must do so many times in Chinese (duì bu duì?). We don't feel right saying someone's name with a rising tone as if we can't remember whether it was her or not.

Unfortunately, to really speak Chinese means saying the tones properly, the way Chinese people say them. But the first step is admitting we have a problem, right? Ok, only 11 more steps to go...

Posted by Albert at 3:45 AM 1 comments (click here to leave one)

Topics: Pronunciation

People always ask me, "How many Chinese characters do you know?" I resist the urge to include some of my students and proudly answer, "About zero." They're shocked because we're speaking Chinese right now. And, to the Chinese, the language IS the hanzi characters.

But for us laowai, if your goal is to speak Chinese as soon as possible, it's a big waste of time to study the hanzi characters from the beginning. They are, however, useful to acknowledge as a way of organizing vocabulary.

I have a much easier time remembering words if I know what each little piece is. It's also a good way to keep the tones straight.

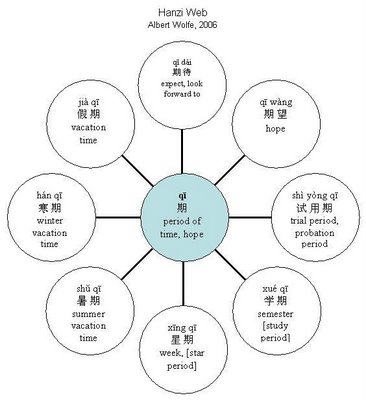

So, to link all those little pieces together, I often visualize something I call a hanzi web. I don't really draw these (that would take forever), this is just an example. But the point is I'm always trying to link the little bits of new vocabulary back to known bits of vocabulary. And the common link (even if you don't know how to draw it) is the hanzi character. It may not make a whole lot of sense, but at least you might have a better chance at remembering the tone.

So, how do you figure out what that dàn in bèndàn is?

picture)

picture)

Posted by Albert at 7:19 PM 0 comments (click here to leave one)

Topics: Vocabulary

Well opinions on that question vary. The US Department of State's Foreign Service Institute has given major foreign languages a rank in order of difficulty to learn for native English speakers. Although the ranking seems to have changed over time from a scale of 1-4 (4 being hardest) to a scale of 1-3, Chinese is invariably given the highest (hardest) score.

But, if you want my humble opinion (and what else is a blog?), I think the reading/writing Chinese hanzi characters is what makes the language hard, and speaking is relatively easy—-kind of. I'll break it down below, but I have to say this first: The best way to learn Chinese slowly is to try to tackle the hanzi characters from the beginning. I've got a whole little article on the subject of hanzi as a pedagological millstone around students' linguistic necks, but since I hope it will influence future Chinese curriculum development in the USA, it’s not quite ready for public viewing.

I’ve created my own scale of 1-10 where:

1 = as easy as I imagine a foreign language could be to learn

10 = as hard as I imagine a foreign language could be to learn

Posted by Albert at 5:12 AM 1 comments (click here to leave one)

Topics: General

| It took Teddi and me about 90 seconds to admit that "Chubby" (as Teddi called him) is the best paper dictionary for an English-speaking laowai who is just starting to learn Chinese. |

But overall, there's no comparison between Chubby and other little dictionaries. If you're going to China and you can only take one book--or only one thing--I suggest it be Chubby.

For my review of an online dictionary click here

Posted by Albert at 12:23 PM 1 comments (click here to leave one)

Topics: Resources

In my first year of studying Chinese I learned (by doing it wrong in front of Chinese friends) that there are rules for where to put tone markings in words with more than one vowel. The official rules, according to Mark Swofford's very helpful site, are:

Posted by Albert at 1:39 PM 3 comments (click here to leave one)

Topics: General

If you've got a handle on basic Chinese and you want to forget that you've got a dictionary in your pocket, I highly recommend bringing Lenny home.

For my review of an online dictionary click here

Posted by Albert at 12:53 PM 0 comments (click here to leave one)

Topics: Resources

There is apparently a tool called Wenlin that let's you type pinyin with tone markings (for example, hǎo). But the easiest way I've found to do it (in small doses) is to copy and paste. I personally have a Word document call "pinyin tones" and that's all that's in it. Click here if you want to see all the pinyin tones so you can copy and paste them.

Otherwise, if you have to do a whole lot of typing pinyin I suggest using this tool by Mark Swofford. It will take "hao3" and convert it to "hǎo". The only bad thing about it is it doesn't remember your line breaks--but I've learned to cope. The settings I use are:

add HTML coding for Web pages? no

output style: code soup

tag style: no <span> tags

If you're looking for something more than that, I suggest checking out Mark's post about Wenlin.

Posted by Albert at 1:00 PM 1 comments (click here to leave one)

Topics: Resources